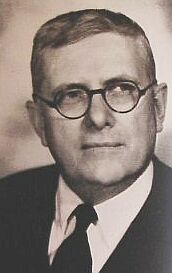

Herbert Evatt

|

|

Herbert Vere Evatt (April 30, 1894 - November 2, 1965), Australian jurist and politician (popularly known as "Doc" Evatt or H V Evatt) was born in Maitland, New South Wales, to a working-class family of Anglo-Irish origin. (He was never called Herbert: his close friends called him Bert, everyone else called him Doc.) After attending Fort Street High School in Sydney, Evatt won scholarships to the University of Sydney, where he graduated in law in 1919. He was unable to serve in the First World War, in which his brother was killed, due to poor eyesight. He became a prominent industrial lawyer in Sydney, working mainly for trade union clients. In 1924 he was awarded the degree Doctor of Law.

In 1925 Evatt was elected as a Labor member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly. He served there until 1930, when the Scullin Labor government appointed him as the youngest-ever justice of the High Court of Australia. He delivered a number of controversial judgements, several of which brought him into conflict with Robert Menzies, who was Attorney-General in the Lyons conservative government. This was the beginning of a life-long mutual dislike.

In 1940 Evatt resigned from the High Court to return to politics, and was elected federal MP for the Sydney seat of Barton. When Labor came to power under John Curtin in 1941, Evatt became Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs (that is, Foreign Minister). He joined the diplomatic councils of the allies during the Second World War, and in 1945 he played a leading role in the founding of the United Nations. He was President of the UN General Assembly in 1948-1949 and was prominent in the negotiations which led to the creation of Israel. He became deputy leader of the Labor Party after the 1946 elections.

In 1949 Labor was defeated by Menzies's new Liberal Party and Evatt went into opposition. When Ben Chifley died in 1951 Evatt was elected Labor leader without opposition. At first his leadership went well, and he campaigned successfully against Menzies's attempt to amend the Constitution to ban the Communist Party. But in the Cold War context this alarmed a section of conservative Catholics within the Labor Party.

Evatt believed he was certain to win the 1954 federal elections, and when he unexpectedly failed to do so (despite polling a slight majority of the vote) he blamed the Catholic group in the party for sabotaging his campaign. He was also convinced that Menzies had conspired with the security services to bring about the Petrov Affair as a means of discrediting him. Declassification of VENONA project archives from July 1995 on revealed that forty years previously the security services had in fact determined that there was a KGB agent in Evatt's office. Although the agent was never identified, the information this agent was able to provide led the security services to suspect either Evatt himself or his private secretary Alan Dalziel.

After the elections Evatt launched a public attack on his enemies in the Labor Party. This precipitated a disastrous split in the party, culminating in the formation of the Democratic Labor Party, a breakway group which directed its preferences against Labor at subsequent elections. This, together with an obsessive hatred of Menzies which led him into many tactical errors, cost Evatt the 1955 and 1958 federal elections, at both of which Labor was heavily defeated. During the 1958 election campaign Evatt made a dramatic offer to resign as leader if the DLP would return to the party, but the offer was rejected.

In 1960 the Labor government in New South Wales appointed Evatt Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, an appointment which was widely seen as a means of giving him a dignified exit from politics. But in 1962 he suffered a nervous breakdown and retired from the bench. He died in Canberra in November 1965. Evatt remains a hero of the Labor movement, despite many attacks on his reputation since his death. It is sometimes asserted that Evatt was insane in his later years but both of his recent biographers refute this.

The Evatt Foundation (http://evatt.labor.net.au/), a research institute affiliated with the Labor Party, is named in his honour.

Further reading

- Ken Buckley et al, Doc Evatt, Cheshire 1994 (a sympathetic biography)

- Peter Crockett, Evatt: A Life, Oxford University Press 1993 (a hostile biography)