|

|

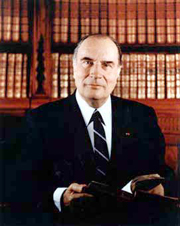

| |

| Office: | President of France |

|---|---|

| Term in office: | May 10, 1981 - May 17, 1995 |

| Preceded by: | Valéry Giscard d'Estaing |

| Succeeded by: | Jacques Chirac |

| Date of birth: | October 26, 1916 |

| Place of birth: | Jarnac |

| Date of death: | January 8, 1996 |

| Place of death: | Paris |

| First lady: | Danielle Mitterrand |

| Party: | Parti Socialiste |

François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand (October 26, 1916 – January 8, 1996; Template:Audio) was a French politician and President of France from May 1981, re-elected in 1988, until 1995.

| Contents |

Early career

Mitterrand was born in Jarnac, Charente. In his youth he was a staunch conservative and an ardent Catholic. His first political act was to join the ultranationalist Croix de Feu, which he did in preference to the larger but equally conservative Action Française due to the proscription of the latter organisation by the Vatican.

Enrolled during WWII, he was made prisoner in 1940 and escaped in 1941. He reached the so-called free zone and joined the Vichy government as a junior minister.

In December 1942, Mitterrand wrote in the official Vichy journal France, revue de l'État nouveau:

- "If France doesn't want to die in the mud, the last French people worthy of this name must declare a merciless war against all who, here or abroad, are preparing to open floodgates against it: Jews, Freemasons, Communists... always the same, and all of them Gaulists."

- "Si la France ne veut pas mourir dans cette boue là, il faut que les derniers français dignes de ce nom déclarent une guerre sans merci à tous ceux qui, à l'intérieur comme à l'extérieur, se préparent à lui ouvrir les écluses : juifs, maçons, communistes...toujours les mêmes et tous gaullistes".

Later he worked with the French Resistance in a group including several Vichy officials, while still holding his ministerial job. Almost until his death, Mitterrand would lay a wreath every year on the grave of Pétain, the head of the Vichy government and a French hero of the First World War; in 1943 he received the Francisque, the honorific distinction of the Vichy regime. When Mitterrand's Vichy past was exposed in the 1950s, he initially denied having received the Francisque.

After the war he quickly moved back into politics, joined a center-left resistance party and was elected as representative for the Nièvre département in 1946. He held various offices in the Fourth Republic before resigning in 1957 over the French policies during the Algerian war of independence. Mitterrand is said to have covered up, as justice minister, various illegal acts, including torture, during the repression of the independence movement.

In 1958, he was one of the few to object to the nomination of Charles de Gaulle as head of government, and lost his seat in the 1958 elections, beginning a long "crossing of the desert". In 1959, on the avenue de l'Observatoire in Paris, Mitterrand escaped an assassin's bullet by diving behind a hedge. The incident brought him a great deal of publicity, boosting his political ambitions. Some of his critics claim that he had staged the incident himself. Prosecution was initiated on the issue, but was later dropped.

In the Fifth Republic he stood in the Presidential elections against Charles de Gaulle in 1965 but was defeated. President of the Left Federation (coalition of socialists and liberals) from 1965 to 1968, he turned to the French Socialist Party (PS), becoming leader of the party by 1971, following the Congress of Epinay. He stood again in 1974 opposite Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and was again defeated.

Presidency

In the French Presidential Election of 1981 he became the first socialist President of the Fifth Republic, and his government the first left-wing government in 23 years. One of his first decisions was to ask Parliament to abolish the death penalty; Parliament also voted in a wealth tax in the first year of his first term as President.

Domestically, his aims were blunted first by a series of financial crises, and then by a conservative parliament (from 1986 to 1988, and 1993 to 1995), although he worked well with Prime Minister Jacques Chirac. Various "great projects" were completed during his Presidency, including the Channel Tunnel, the pyramid at the Louvre (1988), the Grande Arche at La Défense (1989), and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (1995). Mitterrand also presided over the celebrations of the bicentenary of the French Revolution in 1989.

His major achievements came internationally, especially in the European Economic Community. He supported the extension of the Community to Spain and Portugal (who both joined in January 1986) and in February 1986 he helped the Single European Act come into effect. He worked well with Helmut Kohl and improved Franco-German relations measurably. Together they fathered the Maastricht Treaty, which was signed on February 7, 1992.

Because the Left had had a series of defeats in national elections since 1958 when Mitterrand was elected in 1981, he was largely regarded as the savior of the Left and for this reason was highly regarded by many Socialists, perhaps to the point of ridicule (the so-called tontonmania, from tonton, or "uncle", Mitterrand's nickname). Critics contend that this led to complacency and tolerance for Mitterrand's shortcomings: a monarchic style of presidency reminiscent of that of Charles de Gaulle, lack of transparency regarding his early career and his ties to Vichy, and other scandals (see below).

His term as President ended in May 1995. He was succeeded by Jacques Chirac and died of cancer six months later.

His wife, Danielle Mitterrand, is a left-wing militant, with whom he had two sons: Jean-Christophe and Gilbert Mitterrand. He also had a daughter, Mazarine Pingeot; see below. His nephew Frédéric Mitterrand is a journalist, and his brother in law Roger Hanin a well-known actor.

Scandals and controversies of Mitterrand's presidency and death

Following his death, a controversy erupted when his former physician, Dr Claude Gubler, wrote a book called Le Grand Secret ("The Great Secret") explaining that Mitterrand had had false health reports published since November 1981, hiding his cancer. Mitterrand's family then prosecuted Gubler and his publisher for violating medical secrecy.

Mitterrand, a married man, had an affair with Anne Pingeot, out of which a daughter, Mazarine, was born. Mitterrand sought secrecy on that issue, which lasted until November 1994, when Mitterrand's failing health and impending retirement meant he could no longer count on the fear and respect he had once inspired among French journalists. Also, Mazarine, a college student, had reached an age where she could no longer be protected as a minor.

From 1982 to 1986, Mitterrand established an "anti-terror cell" installed as a service of the president of the republic. This was a fairly unusual setup, since such law enforcement missions against terrorism are normally left to the French National Police and French Gendarmerie, run under the cabinet and the Prime Minister, and under the supervision of the judiciary. The cell was largely made from members of these services, but it bypassed the normal line of command and safeguards.

Most markedly, it appears that the cell, under illegal presidential orders, obtained wiretaps on journalists, politicians and other personalities who may have been an impediment for Mitterrand's personal affairs, especially those who may have revealed the situation of Mazarine and her mother. The illegal wiretapping was revealed in 1993 by Libération; the case against members of the cells went to trial in November 2004. [1] (http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3224,36-387334,0.html) [2] (http://www.netscape.qc.ca/article/?cat=Monde&article=M111351AU&ch=a)

External links

- "Mitterrand's Legacy" (http://www.thenation.com/doc.mhtml?i=19960129&s=singer) (1996) in The Nation

- François Mitterrand institute (http://www.mitterrand.org)

- Source of quoted article (http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/France%2C_revue_de_l%27%C3%89tat_nouveau)