Electromagnetic spectrum

|

|

|

| Legend: γ = Gamma rays |

The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses all possible wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation. Electromagnetic energy at a particular wavelength λ (in vacuum) has an associated frequency ν and photon energy E. These quantities are related according to the equations:

- <math>\lambda = c/\nu \,\!<math>

and

- <math>E=h\nu \,\!<math>

where

c is the speed of light (3×108 m/s).

h = 6.626 × 10−34 J·s is Planck's constant, or, in alternative units, h = 4.136 μeV/GHz.

The electromagnetic spectrum, shown in the table, extends from electric power at the long-wavelength end to gamma radiation at the short-wavelength end, covering wavelengths from thousands of kilometres down to fractions of the size of an atom.

In the branch of physics called electromagnetic spectroscopy, the frequency spectra of radiation absorbed and emitted by matter are used to obtain information about matter.

| Contents |

Classifications

While the classification scheme is generally accurate, in reality there is often some overlap between neighboring types of electromagnetic energy. For example, SLF radio waves at 60 Hz may be received and studied by astronomers, or may be ducted along wires as electric power. Also, some low-energy gamma rays actually have a longer wavelength than some high-energy X-rays. This is possible because "gamma ray" is the name given to the photons generated from nuclear decay or other nuclear and subnuclear processes, whereas X-rays on the other hand are generated by electronic transitions involving highly energetic inner electrons. Therefore the distinction between gamma ray and X-ray is related to the radiation source rather than the radiation wavelength. Generally, nuclear transitions are much more energetic than electronic transitions, so usually, gamma-rays are more energetic than X-rays. However, there are a few low-energy nuclear transitions (e.g. the 14.4 keV nuclear transition of Fe-57) that produce gamma rays that are less energetic than some of the higher energy X-rays.

Use of the radio frequency spectrum is regulated by governments. This is called frequency allocation.

Electric power

Electric power covers the low-frequency, long-wavelength end of the spectrum. The radiation is usually ducted along 2-wire and 3-wire transmission lines and sent to various devices besides antennas. At zero frequency the energy is emitted by batteries and DC power supplies, while at 50 Hz and 60 Hz it is produced by rotary magnetic generators and ducted through the international power grids. At frequencies between 20 Hz to 30 kHz the EM energy is translated to and from acoustic energy and is distributed over telephone lines, as well as being used to operate loudspeakers for public address or in music systems. Note that other than its frequency, there is no physical difference between the VHF energy guided along a television coaxial cable, versus the 60 Hz travelling along the cord leading to a light bulb. When connected to the appropriate antenna, both will radiate into space.

Radio frequency

|

Radio spectrum |

Atmospheric_electromagnetic_transmittance_or_opacity.jpg

Main article: radio frequency

Radio waves generally are utilized by antennas of appropriate size, with wavelengths ranging from hundreds of meters to about one millimeter. They are used for transmission of data, via modulation. Television, mobile phones, wireless networking and amateur radio all use Radio Waves.

Microwaves

The super high frequency (SHF) and extremely high frequency (EHF) of Microwaves come next. Microwaves are waves which are typically short enough to employ tubular metal waveguides of reasonable diameter. Microwave energy is produced with Klystron and Magnetron tubes, and with solid state diodes such as Gunn and IMPATT devices. Microwaves are absorbed by molecules that have a dipole moment in liquids. In a microwave oven, this effect is used to heat food. Low-intensity microwave radiation is used in Wi-Fi.

It should be noted that an average Microwave oven in active condition is, in close range, powerful enough to cause interference with poorly shielded electromagnetic fields such as those found in mobile medical devices and cheap consumer electronics.

Currently no efficient sources exist for microwave energy at the high end of the band, sub-millimeter waves or so-called terahertz waves, so this portion of the EM spectrum is relatively unused at present.

Terahertz radiation

Relatively understudied spectrum of light between far infrared and microwaves.

Infrared radiation

The infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum covers the range from roughly 300 GHz (1 mm) to 400 THz (750 nm). It can be divided into three parts:

- Far-infrared, from 300 GHz (1 mm) to 30 THz (10 μm). The lower part of this range may also be called microwaves. This radiation is typically absorbed by so-called rotational modes in gas-phase molecules, by molecular motions in liquids, and by phonons in solids. The water in the Earth's atmosphere absorbs so strongly in this range that it renders the atmosphere effectively opaque. However, there are certain wavelength ranges ("windows") within the opaque range which allow partial transmission, and can be used for astronomy. The wavelength range from approximately 200 μm up to a few mm is often referred to as "sub-millimeter" in astronomy, reserving far infrared for wavelengths below 200 μm.

- Mid-infrared, from 30 to 120 THz (10 to 2.5 μm). Hot objects (black-body radiators) can radiate strongly in this range. It is absorbed by molecular vibrations, that is, when the different atoms in a molecule vibrate around their equilibrium positions. This range is sometimes called the fingerprint region since the mid-infrared absorption spectrum of a compound is very specific for that compound.

- Near-infrared, from 120 to 400 THz (2,500 to 750 nm). Physical processes that are relevant for this range are similar to those for visible light.

Visible radiation (light)

| Color | Wavelength interval | Frequency interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| red | ~ 625 to 740 nm | ~ 480 to 405 THz | ||

| orange | ~ 590 to 625 nm | ~ 510 to 480 THz | ||

| yellow | ~ 565 to 590 nm | ~ 530 to 510 THz | ||

| green | ~ 520 to 565 nm | ~ 580 to 530 THz | ||

| cyan | ~ 500 to 520 nm | ~ 600 to 580 THz | ||

| blue | ~ 430 to 500 nm | ~ 700 to 600 THz | ||

| violet | ~ 380 to 430 nm | ~ 790 to 700 THz | ||

|

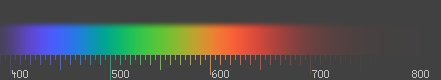

Continuous spectrum |

||||

After infrared comes visible light. This is the range in which the sun and stars similar to it emit most of their radiation. It is probably not a coincidence that the human eye is sensitive to the wavelengths that the sun emits most strongly. Visible light (and near-infrared light) is typically absorbed and emitted by electrons in molecules and atoms that move from one energy level to another. The light we see with our eyes is really a very small portion of Electromagnetic Spectrum. A rainbow shows the optical (visible) part of the Electromagnetic Spectrum; Infrared (if you could see it) would be located just beyond the red side of the rainbow with Ultraviolet appearing just beyond the violet end.

Ultraviolet light

Next comes ultraviolet. This is radiation whose wavelength is shorter than the violet end of the visible spectrum.

Being very energetic, UV can break chemical bonds, make molecules unusually reactive or ionize them, in general changing their mutual behavior. Sunburn, for example, is caused by the disruptive effects of UV radiation on skin cells, which can even cause skin cancer, if the radiation damages the complex DNA molecules in the cells (UV radiation is a proven mutagen). The Sun emits a large amount of UV radiation, which could quickly turn Earth into a barren desert, but most of it is absorbed by the atmosphere's ozone layer before reaching the surface.

X-rays

After UV come X-rays. Hard X-rays are of shorter wavelengths than soft X-rays. X-rays are used for seeing through some things and not others, as well as for high-energy physics and astronomy. Black holes and neutron stars emit x-rays, which enable us to study them.

Gamma rays

After hard X-rays come gamma rays. These are the most energetic photons, having no lower limit to their wavelength. They are useful to astronomers in the study of high-energy objects or regions and find a use with physicists thanks to their penetrative ability and their production from radioisotopes. The wavelength of gamma rays can be measured with high accuracy by means of Compton scattering.

Note that there are no defined boundaries between the types of electromagnetic radiation. Some wavelengths have a mixture of the properties of two regions of the spectrum. For example, red light resembles infra-red radiation in that it can resonate some chemical bonds.

See also

External links

- U.S. Frequency Allocation Chart (http://www.ntia.doc.gov/osmhome/allochrt.html) - Covering the range 3 kHz to 300 GHz (from Department of Commerce)

- Canadian Table of Frequency Allocations (http://strategis.ic.gc.ca/epic/internet/insmt-gst.nsf/vwapj/spectallocation.pdf/%24FILE/spectallocation.pdf) (from Industry Canada)

- UK frequency allocation table (http://www.ofcom.org.uk/static/archive/ra/topics/spectrum-strat/future/strat02/strategy02app_b.pdf) (from Ofcom, which inherited the Radiocommunications Agency's duties, pdf format)

- The Science of Spectroscopy (http://www.scienceofspectroscopy.info) - supported by NASA, includes OpenSpectrum, a Wiki-based learning tool for spectroscopy that anyone can edit

| Electromagnetic Spectrum

Radio waves | Microwave | Terahertz radiation | Infrared | Optical spectrum | Ultraviolet | X-ray | Gamma ray Visible: Red | Orange | Yellow | Green | Blue | Indigo | Violet |

da:Elektromagnetisk spektrum de:Elektromagnetisches Spektrum es:Espectro electromagnético fi:Sähkömagneettinen spektri fr:Spectre électromagnétique id:Spektrum elektromagnetik it:Spettro elettromagnetico nl:Elektromagnetisch spectrum pt:Espectro eletromagnético tr:Elektromanyetik tayf