Egyptian language

|

|

Records of the Ancient Egyptian language have been dated about 3000 BC. It is part of the Afro-Asiatic group of languages and is related to Berber and Semitic (languages such as Arabic and Hebrew). The language survived until the fifth century AD in the form of Demotic and until the Middle Ages in the form of Coptic; its long lifespan of over four millennia makes it one of the oldest recorded languages known to modern human beings.

The official language of modern day Egypt is Arabic, which gradually replaced Egyptian and its descendant, the Coptic language as the language of daily life in the centuries after Egypt was conquered by Arab Muslims. Coptic is still used as a liturgical language in the Coptic Church.

| Contents |

|

|

Development of the Language

Scholars group the Egyptian language into six major chronological divisions:

- Archaic Egyptian (before 2600 BC)

- Old Egyptian (2600 BC - 2000 BC)

- Middle Egyptian (2000 BC - 1300 BC)

- Late Egyptian (1300 BC - 700 BC)

- Demotic (seventh century BC - fifth century AD)

- Coptic (fourth - fourteenth century AD)

It should be noted that Egyptian writing in the form of label and signs has been dated to 3000 BC. These early texts are generally lumped together under the term "Archaic Egyptian."

Old Egyptian was spoken for some 500 years from 2600 BC onwards. Middle Egyptian was spoken from about 2000 BC for a further 700 years when Late Egyptian made its appearance; Middle Egyptian did, however, survive until the first few centuries AD as a written language, similar to the use of Latin during the Middle Ages. Demotic first appears about 650 BC and survived as a spoken language until fifth century AD. Coptic -- the Bohairic dialect is still used by the Egyptian Christian Churches -- appeared in the fourth century AD and survived as a written, living language until the fourteenth century AD; it probably survived in the Egyptian countryside as a spoken language for several centuries after that.

Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian were all written using hieroglyphs and hieratic. Demotic was written using a script derived from hieratic; its appearance is vaugely similar to modern Arabic script (although the two are not at all related). Coptic is written using the Coptic alphabet, a modified form of the Greek alphabet with a number of symbols borrowed from Demotic for sounds that did not occur in Ancient Greek.

Arabic gradually replaced spoken Coptic after the Arabian invasions in the seventh century, though Arabic was the language of the Muslim political administration soon thereafter.

Structure of the Language

Egyptian is a fairly typical Afro-Asiatic language. At the heart of Egyptian vocabulary is a root of three consonants. Sometimes there were only two, for example /r'/ "sun" (where the apostrophe represents a voiced pharyngeal fricative); others, such as /nfr/, which means beautiful; and some could be as large as five /sxdxd/ "be upside-down". Vowels and other consonants were then added to this root in order to derive words, in the same way as Arabic and other Afro-Asiatic languages do today. However, we do not know what these vowels would have been, since like other Afro-Asiatic languages, Egyptian does not write vowels; hence "ankh" could represent either "life", "to live" or "living". In transcription, "a", "i" and "u" all represent consonants; for example, the name Tutankhamen was written in Egyptian "twt 'nkh ymn" (the apostrophe represents a voiced pharyngeal fricative). Experts have assigned generic sounds to these values in order to fake a pronunciation. Unfortunately, this convention has often been mistaken for actual pronunciation.

Phonologically, Egyptian contrasted bilabial, labiodental, alveolar, palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal and glottal consonants, in a distribution rather similar to that of Arabic.

Egyptian's basic word order is Verb Subject Object; where we would write "the man opens the door", Egyptians would say "opens the man the door".

Regarding morphology, Egyptian uses the so-called status constructus construction to combine two or more nouns, more or less like any Semitic language. With this construction, the first noun is sometimes changed - e.g. final -h in feminine nouns becomes -t. Example: mlkt shba "The Queen of Saba", the original form of mlkt being mlkh. The early stages of Egyptian possessed no articles, no words for "the" or "a"; later forms used the words /p3/, /t3/ and /n3/ for this purpose (where 3 represents a glottal stop.) Egyptian uses two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine, similarly to Romance languages and Irish Gaelic; it also uses three grammatical numbers: like many other Afro-Asiatic languages, it contrasts singular, dual and plural forms. When saying something like "the man is red", the word "red" (dSrt in Egyptian) acts as a predicative verb.

Egyptian Writing

Overview

Most people refer to hieroglyphs when they speak about Egyptian writing. It is a common misconception that the hieroglyphs are pictures that represent ideas instead of the sounds of the language. While the shapes of the hieroglyphs are indeed taken from real (or imaginary) objects, most of them are used for their phonetic value. Take, e.g., the hieroglyph representing a house. It can be used to write the word pr (vowels unknown, see below) which means 'house'. The same hieroglyph is used for the word prj 'to come out' due to the similarity in pronunciation. To leave no doubt as to which word was actually meant, the Egyptian scribe would add a pair of walking legs underneath the house to clarify that prj and not pr was meant here. To further clarify the pronunciation, the hieroglyph for mouth (ro) is typically added in between the house and the walking legs, so that the whole combination encodes the word prj like this: "Word that sounds like a word for house which ends in an r and is related to walking => to come out". Hieroglyphic writing is thus an intricate mixture of phonetic and semantic components.

Apart from the hieroglyphs, hieratic (a cursive version of hieroglyphic writing) and demotic (even more cursive and abbreviated) were employed in Egypt's 3,000 years history of hieroglyphic writing. As Egypt became part of the Greek and (later) the Roman empire, the hieroglyphic writing system was replaced by the Greek alphabet used first to write magical and later Christian manuscripts (Coptic). A few extra characters had to be added to represent sounds of the Egyptian language which did not exist in the Greek pronunciation of the time (like, e.g. the "f"). These characters were taken from demotic. Thus, a few Egyptian hieroglyphs continue to be used onto this day in the Coptic church.

Hieroglyphs

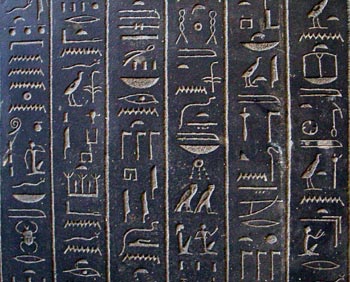

Hieroglyphs from the

Black Schist sarcophagus of Ankhnesneferibre.

Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, about 530BC, Thebes.

The British Museum, London, UK.

Hieroglyphic Usage

Hieroglyphs were used for most of the surviving forms of written communication during the Old and Middle Egyptian eras, at least for official documents; hieratic was already being used for day-to-day administrative needs during the Old Kingdom. Religious texts during the Demotic era were also typically written in hieroglyphs when they were inscribed on temple walls and stelae; hieratic was used for religious documents on papyrus. (Administrative works were of course written in Demotic.) The last datable hieroglyphic text was written in 394 AD.

Hieroglyphic Syntax

As explained previously, the majority of hieroglyphs seen in any particular text do not represent the objects they depict. They mostly represent sounds or were used as "determinatives" to show what type of word was being used. Hieroglyphic could be written in the following ways:

- horizontal, left-to-right

- horizontal, right-to-left

- vertical, facing left-to-right

- vertical, facing right-left

Written, cursive hieroglyphic is generally written in columns, top-to-bottom or horizontally, right-to-left. In the latter stages of hieroglyphic cursive the only surviving examples are written horizontally, right-to-left; vertical hieroglyphic should be read from top-to-bottom.

It is generally an easy task to determine which way to read the hieroglyphs even if you are unable to understand their meaning. Hieroglyphs with a definite front and back (for example, a person) will generally:

- face the beginning of the sentence

- face the same direction as any person or large object in a picture they describe

As an example, if a tableau contains a picture of a man seated and facing right, then all the hieroglyphs with a definite front and back would face to the right as well. The actual hieroglyphs would be read from right-to-left because these images almost always face the beginning of the sentence.

Hieroglyphic texts that do not display this behaviour are said to be in retrograde. Once one understands hieroglyphic it is easy to determine if one is examining a retrograde text because it will simply make no sense at all!

As an aid to reading, and perhaps to the Ancient Egyptian's sense of aesthetics, hieroglyphs were also packed together into neat patterns. In general, two or more short or thin (depending on which direction one was writing the hieroglyphs) would be written in the same block as each other. Occasionally, a tall or wide symbol would be made smaller and placed with another short or thin hieroglyph.

Finally, hieroglyphic had no standard punctuation. Religious texts generally have no punctuation at all, whilst texts from the latter part of the Ancient Egyptian language have full stops between important lines of thought.

How Hieroglyphic Writing was Deciphered

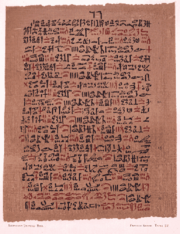

DemoticScriptsRosettaStoneReplica.jpg

Until recently, given the time span we are talking about, the decipherment of hieroglyphic was hampered because those attempting to decipher the hieroglyphs assigned emotional meanings to the actual symbols used. For example, some people believed that the hieroglyph for son, a goose, was chosen because geese love their sons above all other animals. This hieroglyph was chosen, though, simply because the word for goose once had the same sound as the word for son. A further impediment was the lack of complementary material, that is to say material of the same work written in close proximity to another translation.

Athanasius Kircher, a student of Coptic, developed the notion that this last stage of Egyptian could be related to the earlier Egyptian stages. Because he was not able to transliterate or translate hieroglyphic he could not prove this notion. However, in 1799 when the discovery of the Rosetta Stone occurred, scholars finally had an example of hieroglyphic, demotic and Ancient Greek that they were all reasonably certain were the translations of the same passage. In hieroglyphic, the name of the King or Pharaoh and God's names are often placed within a circle called a cartouche. Jean-François Champollion, a young French scholar, demonstrated how the name Kleopatra could be made in hieroglyphic. Furthermore, by using an impressive knowledge of Coptic he surmised that a number of symbols showing everyday objects could be pronounced as in Coptic.

Applying this knowledge to other, well-known hieroglyphic sources clearly confirmed Champollion's work and linguistic scholars now had a way to work with and delineate the language into nouns, verbs, prepositions and other grammatical parts.

Modern Day Resources

Interest in the Ancient Egyptian languages continues. For example, it is still taught in several universities. Many resources are in French or German and not just English so it can be useful to know one of these languages though not a requirement.

For the film Stargate, an Egyptologist was commissioned to develop a constructed language to simulate the tongue of ancient Egyptians living alone in another planet for millennia.

While Egyptian culture is one of the influences of Western civilization, few words of Egyptian origin remain in English. Even those associated with Ancient Egypt were usually transmitted in Greek forms.

Related Articles

- Coptic language

- Demotic

- Egyptian hieroglyph

- Egyptian languages

- Egyptian numerals

- Hieratic

- Hieroglyph

- Transliteration of ancient Egyptian

External links and references

- This book details Middle Egyptian grammar: Allen, J. P. 2000. Middle Egyptian - An Introduction to the Language and Culture of the Hieroglyphs. First Edition. Cambridge University Press. United Kingdom.

- There are online resources at: http://www.rostau.org.uk/de:Altägyptisch