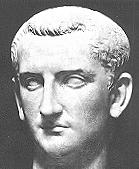

Domitian

|

|

Titus Flavius Domitianus (24 October 51 – 18 September 96), commonly known as Domitian, was a Roman emperor of the gens Flavia.

Domitianus was the son of Vespasian, by his wife Domitilla, and brother of Titus, whom he succeeded in 81.

| Contents |

Early life

Domitian was born in Rome while his father was still a politician and military commander. He received the education of a young man of the privileged senatorial class. He studied rhetoric and literature, publishing some of his writings, law and administration. In his biography Suetonius describes him as a learned and educated adolescent, with elegant conversation. Unlike his brother, Titus, who was much older than himself, Domitian did not accompany their father in his campaigns in the African provinces and Judea.

During the year of the four emperors (AD 69), Domitian assumed a cautious, discreet position, but moved immediately to the imperial palace once his father was proclaimed emperor. He was the representative of the Flavius family in the senate prior to Vespasian and Titus' arrival in Rome. With the rise to power of his father, Domitian grew bolder.

In 70 he managed to force the divorce of Domitia Longina in order to marry her. Lucius Aelius Lamia, her husband, could not prevent the prince's will, and so Domitia became daughter in law of the emperor. Despite its initial recklessness, the alliance was very prestigious for both sides. Domitia Longina was the only daughter of general Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, one of the victims of Nero's terror, remembered as a worthy commander and a honoured politician. They had a son in 71 and a daughter in 74, but both died young. The marriage was far from being traditional: Domitian was a notorious womaniser and his wife was not jealous. Some sources refer that she would join Domitian in his escapades with his mistresses.

As a second son, Domitian was spared from responsibilities. He held several honorary consulships and several priesthoods but no office with imperium. During the reign of his brother Titus, his situation remained essentially the same, since nobody saw him as future emperor. But Domitian certainly had his ambitions. When Titus was dying, he managed to be hailed as his successor by securing the Praetorian Guard's support.

Emperor

As an administrator, Domitian soon proved to be a disaster. The economy first came to a halt and then went into recession, forcing him to heavily devaluate the denarius (silver currency). To further compensate for the economic situation, taxes were raised and discontent soon followed. Due to his love of the arts and to woo the population, Domitian invested large sums in the reconstruction and embellishment of the city, still suffering the effects of the great fire of Rome in 64 and the civil war of 69. Around fifty new buildings were erected and restored, including the Temple of Jupiter in the Capitoline Hill and a palace in the Palatine Hill.

In 85, Domitian nominated himself perpetual censor, the office who held the task of supervising Roman morals and conduct, a task he could hardly apply to himself. By 83, his own marriage was in rupture with continuous infidelities and scandals on both sides. In this year, Domitia Longina was caught with her lover, the actor Paris. The man was executed and the empress was exiled after a hasty divorce. In the next year he developed a passion for his niece Julia Flavia (daughter of Titus) and, like in his first marriage, he kidnapped the girl by dismissing her husband. Julia Flavia died in 91 during an abortion, being deified afterwards. After this, Domitia Longina was recalled to the palace as Roman empress, despite the fact that Domitian never remarried her.

Domitian's greatest passions were the arts and the games. He finished the Colosseum, started by his father, and implemented the Capitoline Games in 86. Like the Olympic Games, they were to be held every four years and included athletic displays, chariot races, but also oratory, music and acting competitions. The Emperor himself supported the travels of competitors from the whole empire and attributed the prizes. He was also very fond of gladiator shows and added important innovations like female and dwarf gladiator fights.

As a military commander, Domitian was not gifted, due to his education in Rome, away from the legions. Probably because of this, the emperor limited Roman military enterprises during his reign. He claimed several Roman triumphs, namely over the Chatti and in Britain, but they were only propaganda manoeuvres, since these wars were still being fought. Nevertheless, several campaigns were fought during his reign, especially in the Danube frontier against the Dacians. Domitian also founded Legio I Minervia in 82, to fight against Chatti.

Towards the end of his reign, which had started with moderation, Domitian revealed a cruel personality. According to several sources, despite some arguments in the academic community, Jews and Christians were heavily persecuted during his reign. The emperor also developed a paranoid fear of persecution that led him to kill or execute several members of the senatorial and equestrian orders. He disliked aristocrats and had no fear of showing it, withdrawing every decision-making power from the Senate.

Domitian was murdered in September 96, in a plot organized by his enemies in the Senate, Stephanus (the steward of the deceased Julia Flavia), members of the Pretorian Guard and empress Domitia Longina. The emperor knew that, according to an astrological prediction, he would die around noon. Therefore, he was always restless during this time of the day. In his last day, Domitian was feeling disturbed and asked a servant boy what time it was several times. The boy, included in the plot, lied, saying that it was much later. More at ease, the emperor went to his desk to sign some decrees, where he was stabbed eight times by Stephanus.

Domitian was succeeded by Nerva (by appointment of the senate), the first of the Five Good Emperors.

Domitian and Early Christianity

For scholars, it is difficult to uncover Domitian's exact policy towards the developing Christian community. It is generally agreed upon that he was the Emperor during the time that the Revelation to John was authored (95 or 96 C.E.). From a Christian perspective, the Revelation, the final canonical book of the New Testament, reveals God's plan for the Apocalypse. From an objective viewpoint, the Revelation could be viewed as a reaction to the anti-Christian policies of Domitian and some earlier emperors. At the time, Christianity was a struggling religion attempting to find a foothold in the classical world. In addition to sporadic persecutions Christians were also facing pressure to conform to the Imperial Cult of Domitian. Although it is unclear that Domitian officially enforced adherence to the cult, scholars generally agree that Roman governors forced citizens to participate in order to prove their loyalty and patriotism. Since Christian doctrine specifically forbids the worship of false idols, Christians refused to partake in this Imperial tradition. In the face of adversity many Christians may have been doubting their beliefs and may even been on the verge of abandoning Christianity all together. In this atmosphere it is conceivable that John of Patmos wrote the Revelation in hopes of inspiring fledgling Christians to persevere. Within the book several symbolic references are made about the Roman Empire and the incumbent Emperor, most likely Domitian. In short, Christians are reminded that their savior will return to reward those who believe and punish those who do not and those who stand against believers.

External link

- Life of Domitian (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Suetonius/12Caesars/Domitian*.html) (Suetonius; English translation and Latin original)

| Preceded by: Titus | Roman Emperor 81–96 | Succeeded by: Nerva |