Robert Falcon Scott

|

|

Captain Sir Robert Falcon Scott (June 6, 1868 - March 29, 1912) was a British Naval officer and Antarctic explorer. Having narrowly failed to be the first to reach the South Pole, beaten by Roald Amundsen and his party, Scott and his party died on the Ross Ice Shelf whilst trying to return to the safety of their base. Scott has become the most famous hero of the "heroic age" of Antarctic exploration.

| Contents [hide] |

Early career

Scott was born in Devonport, England. He left home at the age of thirteen to join the naval vessel HMS Britannia at Dartmouth and begin his training. Scott joined the navy as a midshipman in 1881, first sailing on Boadicea, the flagship of the English Channel fleet at that time. After numerous postings around Britain and North America, Scott rose to become a lieutenant in 1891, specializing in torpedoes.

Discovery expedition 1900-1904

At the behest of Sir Clements Markham, the former polar explorer and then President of the Royal Geographical Society, Scott commanded the National Antarctic Expedition which began in 1900. The major achievements of the expedition were an exploration of the Ross Sea, the land to the east of the ice sea was sighted for the first time and named "King Edward VII Land" in honour of the then British monarch and a new "furthest south" was achieved. Scott, Ernest Shackleton and Dr Edward Wilson reached 82°17′ S on December 31 1902.

Rivalries with Shackleton and Amundsen

It was during the Discovery expedition that Scott met and explored with Ernest Shackleton, who served as his third lieutenant. Many subsequent biographers of both men wrote of an intense personal animosity and rivalry between the two. However Ranulph Fiennes, in his biography of Scott published in 2003, writes that there was in fact little evidence of this and that the two were friendly on the expedition. Fiennes dismisses the autobiography of Albert Armitage, Scott's navigator and second-in-command on the trip, whose account provides most of the primary source data of the split between Scott and Shackleton because Armitage, Fiennes says, felt slighted by Scott. Fiennes writes that Shackleton was sent home early (on the first relief ship) from the Discovery expedition only because he was ill, as Scott claimed, rather than because of a strained relationship between the two, as others have suggested. Scott and Shackleton both went on to organise and lead subsequent expeditions, and therefore found themselves in competition for experienced personnel and financial support.

At that time, there was a widely held view that the first explorer to reach a particular wilderness area obtained territorial rights over further exploration of that area. Shackleton therefore made a promise to Scott not to use the Discovery expedition base at McMurdo Sound, but was forced by circumstances to break this promise on his 1907 expedition, which Scott certainly resented. The same sense of ownership was at the root of the contempt felt by the British explorers for Roald Amundsen's "dash to the Pole" in 1911; the British felt that prior attempts on this goal gave them the sole right to discover the South Pole, and that Amundsen was intruding on this right. There was also resentment over the fact that Amundsen did not declare his objective in the early planning stages of his expedition; the British explorers regarded this as underhand and dishonest behaviour. Such tensions and ill-feeling arose out of an attitude that was common at a time of national pride, and which would simply not be an issue today.

Terra Nova expedition 1910-1912

Inspired partly by the wish to improve his family's fortunes, Scott became obsessed with the idea of being first to the South Pole, which he saw as an important and necessary achievement for his country. After his marriage to Kathleen Bruce on September 2nd 1908, and the birth in 1909 of his only son, Peter Scott, he embarked on his second polar expedition. His ship, Terra Nova (ship), left London on June 1 1910, sailing via Cardiff, which it left on June 15th. Scott sailed with the ship only as far as Rotherhithe and then returned to London to continue raising money for the expedition, and departed a month later to join the ship in South Africa.

Informed en route that Roald Amundsen was also going South, Scott found himself in a race with the Norwegian to be first to reach the Pole. On arriving at the Pole January 17-18, 1912, with a five-man party (Scott, Lieutenant Bowers, Dr Wilson, Petty Officer Edgar Evans, Lawrence Oates), Scott found that Amundsen had been there a month earlier. Amundsen returned to his base in good order, while Scott's entire party perished while returning from the Pole in conditions of extreme cold that have only been recorded once more since the introduction of modern weather stations in the 1960s.

The first to die was Evans, who was injured in a fall and suffered a swift mental and physical breakdown. A little later, Oates, who was afflicted by frostbite, had lost the use of one foot. He was also suffering from an old war wound, and deteriorated to the extent that he was holding back the rest of the party. Gradually becoming aware of the burden he was placing on the others and the fact that he had no chance of survival, Oates voluntarily left the tent and was never seen again.

The bodies of the remaining three members of Scott's party were found six months later in their camp, only eleven miles (20 km) from a massive depot of supplies. With them were their diaries detailing their demise. Scott's journal contains the famous entry: 'Had we lived I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman'. It ends with the words, 'We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker of course and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more. For God's sake, look after our people. R. Scott'.

After his death: the legend of "Scott of the Antarctic"

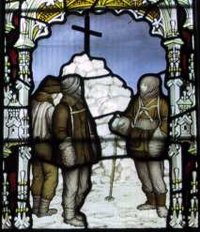

News of Amundsen's success reached Europe before Scott's fate was known. When the tragic story was published, the "tale of hardihood, endurance and courage" did indeed stir the hearts of Englishmen. The powerful and eloquent diary became a bestseller, and Scott was rapidly elevated to legendary status, becoming the Royal Navy's greatest hero since Horatio Nelson, and Britain's first great hero of the twentieth century. Captain Oates, who had sacrificed himself with the famous last words "I am just going outside - I may be some time", ranked second only to Scott in heroic status. The example of Scott, Oates and the others facing death with a stiff upper lip after their superhuman efforts were overwhelmed by the forces of nature, was uncritically celebrated in books and films; Scott was posthumously knighted, and a statue of him by his wife, Kathleen, a sculptor, was erected in London, at Waterloo Place. Scott's brother-in-law, the Reverend Lloyd Harvey Bruce, was the rector of the tiny Warwickshire village of Binton, and he commissioned a large stained glass memorial window, showing scenes from Scott's expedition, which still exists today. A large and recently refurbished memorial to Scott can be found in Plymouth, England overlooking the harbour. It is engraved with words from Scott's journal. Other notable memorials can be found in Christchurch and Port Chalmers, New Zealand, the Terra Nova's last two ports of call before sailing for Antarctica. Scott's very name was extended to encompass the continent where he died, and even today he is still referred to as "Scott of the Antarctic". When a permanent research base was established at the Pole, it was named Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station.

The dramatic end of the Polar journey compensated the British nation for losing the prestige of discovering the South Pole to a Norwegian. A nation which celebrates its heroic failures as much as its triumphs, Britain gained a tragic legend which was cherished even more highly than the simple geographic achievement alone would have been, and it was undiminished by the far greater tragedy of World War One which soon followed. The legend and its central hero went more or less unchallenged for sixty years, until revisionist historians began to deconstruct it. In particular, a ruthless comparative biography ("Scott and Amundsen/The Last Place on Earth", 1979) by Roland Huntford, set out to destroy the legend and to criticise Scott's motivation, leadership, judgement and competence. Coming at a time when the values Scott exemplified were no longer so widely respected (doing things the hard way; keeping a stiff upper lip to the end; flag-planting colonial style exploration; naming discovered territory after the King; uncomplicated patriotism and "muscular Christianity"), the revisionist view gained ground and began to replace the original legend as the most widely accepted view, prompting modern Polar explorer Ranulph Fiennes to write a defence of Scott's reputation ("Captain Scott", 2003).

The debate

Huntford was by no means the first to compare Scott's and Amundsen's expeditions. Apsley Cherry-Garrard's "The Worst Journey in the World", published in 1922 (and widely viewed as one of the greatest travel books ever written), made the direct comparison and gave Amundsen due credit for getting the major decisions right - taking a small team, his mastery of dog driving, and the skiing expertise of his men, for example - and for bringing his party home safely. However, Cherry-Garrard remained loyal to Scott in all personal respects. The revisionists are distinguished by the level of personal criticism of Scott's character.

Revisionists have argued that Scott was over-promoted when he was given command of the Discovery expedition, as he was a relatively junior torpedo officer with no Arctic experience. As evidence of this, they point out that he got the Discovery frozen into ice so firmly that it was nearly lost. But it is the style of land travel which attracts the sternest attacks.

Scott's insistence on first using Siberian ponies and then man-hauling his goods to the Pole, instead of making full use of sled dogs is the single most obvious difference between the two expeditions. Scott did use dogs, but only as far as the Beardmore Glacier, whereas Amundsen, a more experienced dog-driver, took them all the way to the Pole. Perhaps this unwillingness to take dogs further was because of Scott's admitted abhorrence of killing dogs and then feeding them to others. Fiennes' biography suggests that Scott simply used the method which worked best for him, as man-haul had in the Discovery expedition. However, Scott's own diary makes it clear that he believed the heavy manual labour of sledge-hauling was morally superior to the use of dogs, and this prejudices him towards the more inefficient method. His mind was not closed to alternatives, though; he made the first serious attempt to use motorised tractors, correctly recognising that this would be the future of ice travel.

Critics have also pointed out the Englishmen's distaste for learning from the indigenous peoples of the Arctic - the undoubted experts at cold climate survival - as Amundsen had done. That criticism would be more precisely levelled at the Royal Navy rather than Scott himself who never visited the Arctic. He took his advice from his forerunners and superiors in the Navy who had not learnt as much as others such as Amundsen in Norway and Robert Peary in the United States from the native Inuit. But, looking at photos of Scott's team in their canvas outer clothing, you can almost feel the cold. The fact that Scott nearly reached safety means that you can point to any single factor and suggest that it alone could have made all the difference; maybe they would have survived had they been equipped with Inuit-style fur clothing, or had a better diet, or learned better ski technique, or travelled lighter.

The precise cause of Scott's death is also the subject of much debate. It is likely that starvation, exhaustion, extreme cold, and scurvy (a dietary deficiency disease) all contributed to the death of Scott and his men, as did more general strategic factors such as poor planning for contingencies, Scott's last-minute decision to take five men to the Pole rather than the originally planned four; but mostly, it was plain bad luck with the weather. The low temperatures they encountered on the Ross Ice Barrier meant that their sledge would not slide easily over the snow in the familiar way. Their task can be better compared to pulling a full bathtub across the Sahara. Scott and his meteorologist, Simpson, had estimated that the temperatures would be high enough to allow the sledge to slide more easily. In average years, they would have been right, but they were caught in the worst case scenario and had no hope.

Scott also made a great virtue of his dedication to science. While Amundsen set out only to reach the Pole and get back alive, Scott's entire expedition was primarily scientific. Even as they were dying, Scott and Wilson stopped to pick up geological samples, of which they were hauling over 30lb. when they died. Although the dual motivation necessarily compromised the already wafer-thin safety margins of the trek, the science was important. Among the samples found with Scott was a lump of coal from the Trans-Antarctic mountain range, which proved that the continent must have had a warm climate in the distant past. This discovery was of major geological importance and added to the weight of evidence which eventually resulted in the modern theory of plate tectonics. The dying men also kept meteorological records until near the end. The difference of focus between the two expeditions highlights the very different approaches and judgements made by their respective leaders.

External links

- Southern Polar exploration - Robert Falcon Scott (http://www.art-mitchell.freeserve.co.uk/scott/preface.html)

- Secrets of the Dead - Tragedy at the Pole (PBS) (http://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/case_southpole/index.html)

- Substantial resource of polar exploration accounts and memorabilia (http://www.south-pole.com)

eBooks on Project Gutenberg

- Template:Gutenberg by Apsley Cherry-Gerard

- Template:Gutenberg by Captain R. F. Scott

References

bg:Робърт Скот da:Robert Falcon Scott de:Robert Falcon Scott nl:Robert Falcon Scott it:Robert Falcon Scott ja:ロバート・スコット no:Robert Falcon Scott pl:Robert Falcon Scott pt:Robert Falcon Scott fr:Robert Falcon Scott sl:Robert Falcon Scott zh:罗伯特·斯科特