Siege of Veracruz

|

|

Template:Battlebox The Battle of Veracruz was a 20-day siege of the key Mexican seaport of Veracruz, Veracruz, during the Mexican-American War. Lasting from March 9 to March 29, 1847, it began with the first large-scale amphibious assault conducted by United States military forces, and ended with the surrender and occupation of the city. US forces then marched inland to Mexico City.

| Contents [hide] |

Background

After the battles of Monterrey and Buena Vista, fighting in northern Mexico subsided. Much of Zachary Taylor's Army of Occupation was transfered to the command of Major General Winfield Scott. After deliberating on the next course of action, Scott and other Washington officials came to the agreement that a landing would be made at Veracruz, which would provide a staging point for a further advance inland.

Forces

U.S.

Scott had under his command 12,000 troops in 3 divisions for the expedition:

- 1st Divisions of Regulars – William J. Worth

- 2nd Division of Regulars – David E. Twiggs

- 3rd Division of Volunteers – Robert Patterson

Worth's and Twiggs' regulars had previously seen action at the battle of Monterrey and two of Patterson's brigade were commanded by two generals with notable skill: John A. Quitman and James Shields. Also included in the expedition was a brigade of cavalry under William S. Harney. Offshore bombardment was to be provided by the navy under Commodore David Conner. Scott requested special landing crafts for his expedition and the first ever were constructed in Philadelphia by George M. Totten.

Mexican

Veracruz was considered to be the strongest fortress in the western hemisphere at the time. Brigadier General Juan Morales commanded a garrison of 3,360 men which manned three major forts guarding Veracruz:

- Fort Santiago – south end of town

- Fort Concepción – north end of town

- Fort San Juan de Ulúa – offshore on the Gallega Reef

The city itself was completely surrounded by a 15-foot (4.5 m) wall. The defenses contained about 235 guns, 135 of these in Fort Ulúa alone. It was believed that even if the city fell, Ulúa could hold out much longer bottling up the city's port. Because Morales' garrison was small in numbers he decided not to risk the American forces in open battle and instead stayed within the fortresses. In doing so he left the beaches unguarded which offered an inviting target for Scott's army.

Landings

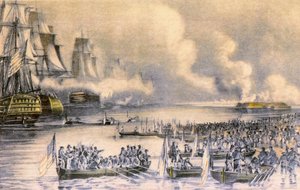

The American Army/Navy force arrived off Veracruz in early March. Scott surveyed the defenses and concluded that the city would not fall to an artillery bombardment alone. He selected the landings to take place at Collado Beach 3 miles (5 km) south of Veracruz. The 1st Regular Division under Worth was chosen to make the landing. Connor's ships moved to within 90 yards of the beach to supply covering fire if necessary. At 3:30 on March 9 the 1st Division in the specialized landing crafts was rowed ashore. Just before the main force touched the beach, a gig dashed ahead and General Worth jumped out into shoulder deep water and waded ashore, to be the first man on the beach. Worth's whole division landed without firing a single shot or receiving a single shot. By 23:00 on that first day, Scott's entire army had been brought ashore: the first large scale amphibious landing conducted by the U.S. military was a success.

The Siege

Encirclement

Once ashore Patterson's division began marching northward to effect a complete encirclement of the city. One of Patterson's brigades under Gideon J. Pillow drove off a Mexican cavalry at Malibran, cutting off the city's water supply. Quitman and Shields both managed to drive off further cavalry charged to prevent the investment. Three days later the U.S. had completed a 7 mile (12 km) siege line from Collado in the south to Vergana in the north.

Investment

A norther blew in and prevented Scott from landing his siege guns for a time. In the meantime the besiegers were plagued by sorties from the city and guerrilla attacks. Colonel Juan Aquayo used the cover of the storm to slip the Alvarado garrison into Veracruz. General Patterson expressed his opinion that the city should be taken by storm. Scott declined such a notion stating he wished to lose no more than 100 men. On the 18th the artillery arrived and Scott concluded he could reduce the city with what he had, but not Fort Ulúa. On March 21, Commodore Matthew C. Perry, Conner's second-in-command, returned from Norfolk, Virginia, after making repairs on the USS Mississippi, with orders to replace Conner in command of the squadron. Perry and Conner met with Scott regarding the navy's role in the siege and Perry offered 6 guns that were to be manned by sailors from the ships. Back onshore under the direction of Captain Robert E. Lee a battery emplacement was constructed 700 yards from the city walls with the army and naval siege guns put in place. On March 22 Morales declined a surrender demand from Scott and the American batteries opened fire. The Mexican batteries responded with accuracy, although few Americans became casualties because of it. Congreve rockets were fired into the defenses and started a fire in Fort Santiago which drove the Mexican gunners from their post. Mexican morale began to drop.

On March 24, Persifor F. Smith's brigade captured a Mexican soldier with reports that Antonio López de Santa Anna was marching an army from Mexico City to the relief of Veracruz. Scott dispatched Colonel Harney with 100 dragoons to inspect any approaches that Santa Anna might make. Harney reported about 2,000 Mexicans and a battery not far away and called for reinforcements. General Patterson led a mixed group of volunteers and dragoons to Harney's aid cleared this force from their positions.

Surrender

With reports such as these Scott grew impatient with the siege and began planning for an assault on the city. On March 25, the Mexicans called for a cease-fire to discuss surrender terms. Mexican officials pleaded that the women and children be let out of the city. Scott refused, believing this to be a delaying tactic and kept up the artillery fire. On March 25 Morales' second-in-command General José Juan Landero stepped in to save his commander the disgrace of surrender, called for a truce with the invaders. A three day negotiation followed in which the Mexicans were able to receive terms which helped to save face. On March 29 the Mexicans officially surrendered their garrisons in Veracruz and Fort Ulúa. That day the U.S. flag flew over San Juan de Ulúa.

Results

Twelve days of bombardment resulting in the surrender of Veracruz opened the east coast of Mexico to U.S. forces. Scott had kept his promise of minimal casualties: 13 killed. Another factor Scott had less control over was the yellow fever that had begun to settle in on his army. However Scott still began immediate plans to leave a small garrison at Veracruz and march inland, his first objective being Xalapa. Along the way Scott would in fact encounter a sizable Mexican army under Santa Anna at the battle of Cerro Gordo.

Sources

- Bauer, K. Jack, "The Mexican-American War 1846-48"

- Nevin, David; editor, The Mexican War (1978)

- It Ain't New (http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/apj/apj00/fal00/skelton.htm)

- www.aztecclub.com (http://www.aztecclub.com/main-art.htm)