Architecture of Ancient Greece

|

|

This article discusses architecture in Ancient Greece. Architecture (building executed to an aesthetically considered design) was extinct in Greece from the end of the Mycenaean period (about 1200 BC) until the 7th century, when urban life and prosperity recovered to a point where public building could be undertaken. But since most Greek buildings in the Archaic and Early Classical periods were made of wood or mud-brick, nothing remains of them except a few ground-plans, and there are almost no written sources on early architecture or descriptions of buildings. Most of our knowledge of Greek architecture comes from the few surviving buildings of the Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods (since Roman architecture heavily copied Greek), and from late written sources such as Vitruvius (1st century AD). This means that there is a strong bias towards temples, the only buildings which survive in any number.

Architecture, like painting and sculpture, was not seen as an “art” in the modern sense for most the Ancient Greek period. The architect was a craftsman, employed by the state or a wealthy private client. There was no distinction between the architect and the building contractor. The architect designed the building, hired the labourers and craftsmen who built it, and was responsible for both its budget and its timely completion. He did not enjoy any of the lofty status accorded to modern architects of public buildings. Even the names of architects are not known before the 5th century. An architect like Iktinos, who designed the Parthenon, who would today be seen as a genius, was treated in his lifetime as no more than a very valuable master tradesman.

The standard format of Greek public buildings is well known from surviving examples such as the Parthenon, and even more so from Roman buildings built partly on the Greek model, such as the Pantheon in Rome. The building was usually either a cube or a rectangle made from limestone, of which Greece has an abundance, and which was cut into large blocks and dressed. Marble was an expensive building material in Greece: high quality marble came only from Mt Pentelus in Attica and from a few islands such as Paros, and its transportation in large blocks was difficult. It was used mainly for sculptural decoration, not structurally, except in the very grandest buildings of the Classical period such as the Parthenon.

Missing image Ac.tholos.jpg The Tholos at Delphi |

The basic cube or rectangle was usually flanked by colonnades (rows of columns) on either two or on all four sides. This is the format of the Parthenon. Alternatively, a cube-shaped building would have a columned portico (or pronaos in Greek) forming its entrance, as seen at the Pantheon. The Greeks understood the principles of the masonry arch but made little use of it, and did not put domes on their buildings— these refinements were left to the Romans. The Greeks roofed their buildings with timber beams covered with overlapping terra cotta (or occasionally marble) tiles.

The low pitch of Greek rooves produced a flat triangular shape at each end of the building, the pediment, which was usually filled with sculptural decoration. Along the sides of the building, between the tops of the columns and the roof, was a row of blocks now known as the entablature, whose outward-facing surfaces also provided a space for sculptures, known as friezes, which consisted of alternating metopes and triglyphs. No surviving Greek building preserves these sculptures intact, but they can be seen on some modern imitations of Greek buildings, such as the Greek National Academy building in Athens.

Missing image Ac.theatre.jpg The Theatre of Herodes Atticus, Athens |

The temple was the most common and best-known form of Greek public architecture. The temple did not serve the same function as a modern church. Some temples housed the altar of the god or goddess to whom it was dedicated, but many did not. Temples served as storage places for the treasury associated with the cult of the god in question, as the location of a statue of the god (though this was not an idol in a religious sense), and a place for devotees of the god to leave their offerings, such as dedicated statues. The inner building of the temple, the cella, thus served mainly as a strongroom and storeroom. It was usually lined by another row of columns.

Other common architectural forms used by the Greeks were the tholos, a circular structure of which the best example is at Delphi and which served religious purposes; the propylon or porch, which flanked the entrances to temple grounds and sanctuaries (the best known example is on the Acropolis of Athens); and the stoa, a long narrow hall with an open colonnade on one side, which was use to house rows of shops in the agoras (commercial centres) of Greek towns. A completely restored stoa, the Stoa of Attalus, can be seen in Athens.

Every Greek town of any size also had a palaestra or a gymnasium. These were essentially enclosed spaces, open to the sky and lined with shaded colonnades, used for athletic contests and exercise: they were the social centres for male citizens. Greek towns also needed at least one bouleuterion or council chamber, a large square building which served as both a meeting place for the town council (boule) and as a court house. Because the Greeks did not use arches or domes, they could not build large rooms with unsupported rooves: the bouleuterion thus had rows of internal columns to hold the roof up. No examples of these buildings survive.

Finally every Greek town had a theatre. These were used for both public meetings as well as dramatic performances. These performances originated as religious ceremonies; they went on to assume their Classical status as the highest form of Greek culture by the 6th century BC (see Greek theatre). The theatre was usually set in a hillside outside the town, and had rows of tiered seating set in a semi-circle around the central performance area, the orchestra. Behind the orchestra was a low building called the skene, which served as a store-room, a dressing-room, and also as a backdrop to the action taking place in the orchestra. A number of Greek theatres survive almost intact, the best known being at Epidaurus.

There were two main styles (or "orders") of Greek architecture, the Doric and the Ionic. These names were used by the Greeks themselves, and reflected their belief that the styles descended from the Dorian and Ionian Greeks of the Dark Ages, but this is unlikely to be true. The Doric style was used in mainland Greece and spread from there to the Greek colonies in Italy. The Ionic style was used in the cities of Ionia (now the west coast of Turkey) and some of the Aegean islands. The Doric style was more formal and austere, the Ionic more relaxed and decorative. The more ornate Corinthian style was a later development of the Ionic. These styles are best known through the three orders of column capitals, but there are differences in most points of design and decoration between the orders. See the separate article on Classical orders.

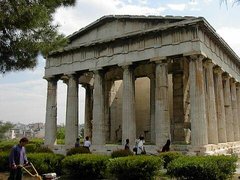

Most of the best known surviving Greek buildings, such as the Parthenon and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, are Doric. The Erechtheum, next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. The Ionic order became dominant in the Hellenistic period, since its more decorative style suited the aesthetic of the period better than the more restrained Doric. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus, can be seen in Turkey, at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. But in the greatest of Hellenistic cities, Alexandria in Egypt, almost nothing survives.