Adoption in Rome

|

|

In ancient Rome, adoption of boys was a fairly common procedure, particularly in the upper senatorial class. The need for a male heir and the expense of raising children were strong incentives to have at least one son, but not too many children. Adoption, the obvious solution, also served to cement ties between families, thus fostering and reinforcing alliances. In the Imperial period, the system also acted as a mechanism for ensuring a smooth succession, the emperor taking his chosen successor as his adopted son.

| Contents |

Causes

As Rome was ruled by a selected number of powerful families, every senator's duty was to produce sons to inherit the estate, family name and political tradition. But a large family was an expensive luxury. Daughters had to be provided with a suitable dowry and sons had to be pushed through the political offices of the cursus honorum. The higher the political status of a family, the higher was the cost. Due to this, Roman families restricted the number of children, avoiding more than three. The six children of Appius Claudius Pulcher (lived 1st century BC) were considered at the time as political suicide. Sometimes, not having enough children proved to be a wrong choice. Infants could die and the lack of male births was always a risk. For families cursed with too many sons and the ones with no boys at all, adoption was the only solution. Even the wealthy Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus did not hesitate in giving his two oldest boys up for adoption, one to the Cornelii Scipiones (Scipio Aemilianus, the winner of the Third Punic War) the other to Quintus Fabius Maximus Cunctator.

Practice

In Roman law, the power to give children in adoption was one of the recognised powers of the pater familias. The adopted boy would usually be the oldest, the one with proved health and abilities. Adoption was an expensive agreement for the childless family and quality had to be ensured. Adoption was agreed between families of (for the most part) equal status, often political allies and/or with blood connections. A plebeian adopted by a patrician would become a patrician, and vice versa; however, at least in Republican times, this required the consent of the Senate (famously in the case of Publius Clodius Pulcher). A sum of money was exchanged between the parties and the boy assumed the adoptive father's name, plus a cognomen that indicated his original family (see Roman naming convention). Adoption was not secretive or considered shameful, nor was the adopted boy expected to cut ties to his original family. Like a marriage contract, adoption was a way to reinforce inter-family ties and political alliances. The adopted child was often in a privileged situation, enjoying both original and adoptive family connections. Almost every politically famous Roman family used it.

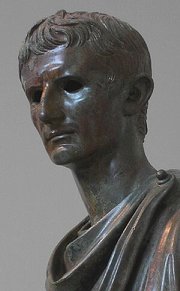

Probably the most famous adopted man in Republican times was Augustus Caesar. Born as Gaius Octavius, he was adopted by his great-uncle Julius Caesar and acquired the name of Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (hence his common name of Octavian). As in the case of Clodius, one could be adopted by a man younger than oneself; his sister Clodia is also the one known example of a Roman woman being adopted.

Although not technically adoption, it was common for a dying man to leave guardianship of his children to another man, thus granting him the power of a paterfamilias over what were now effectively his foster children. Examples include the Dictator Sulla leaving his children in the care of Lucullus, and Mark Antony's children being left in Augustus' care.

Imperial Succession

In the Roman Empire, adoption was the most common way of acceding to the throne without use of force. During the 2nd century, each of the successive Five Good Emperors (except the last, Marcus Aurelius) would adopt an heir from outside his family; the system produced such highly regarded emperors as Trajan and Hadrian. Adoption proved a more flexible and workable tool for orderly succession in the Roman Empire than natural succession did. It guaranteed that people of promise, and often of proven competence, were named as official successors to what was in effect a military dictatorship. By contrast, the succession of Marcus Aurelius' natural son Commodus to the throne proved to be a turning point, marking the beginning of the Empire's steady decline.