Plesiosaur

|

|

| Plesiosaur

Conservation status: Fossil | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

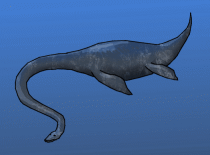

Artistic recreation | ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Families | ||||||||||

|

Cryptoclididae |

Plesiosaurs (PLEE-see-oh-SORES) were large, carnivorous aquatic reptiles. They are somewhat fancifully said to look like "a turtle with a snake threaded through its body", though they lacked a shell.

They first appeared in the late Triassic period and thrived until the K-T extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. Despite being large Mesozoic reptiles, they were not a type of dinosaur.

It is occasionally claimed that plesiosaurs are not extinct, although there is no scientific evidence for this belief; the modern sightings that are occasionally reported are usually explained as basking shark carcasses or hoaxes.

| Contents |

Description

The typical plesiosaur had a broad body and a short tail. They retained their ancestral two pairs of limbs, which evolved into large flippers. Plesiosaurs evolved from the earlier nothosaurs, who had a more crocodile-like body; major types of plesiosaur are primarily distinguished by head and neck size.

As a group, the plesiosaurs were the largest aquatic animals of their time, and even the smallest were about 2 m (6.5 ft) long. They grew to be considerably larger than the largest giant crocodiles, and were bigger than their successors, the mosasaurs. However, their predecessors as rulers of the sea, the dolphin-like ichthyosaurs, are known to have reached 23 m in length, and the modern whale shark (18 m), sperm whale (20 m), and especially the blue whale (30 m) are known from considerably larger specimens.

Behavior

Plesiosaurs have been discovered with fossils of belemnites (squid-like animals), and ammonites (giant nautilus-like molluscs) associated with their stomachs. They had powerful jaws, probably strong enough to bite through the hard shells of their prey. The bony fish (Osteichthyes), started to spread in the Jurassic, and were likely prey as well.

No eggs or evidence of live birth has been discovered, but it has been theorized that smaller plesiosaurs may have crawled up on a beach to lay their eggs, like the modern leatherback turtle.

Another curiosity is their four-flippered design. No modern animals have this swimming adaptation, so there is considerable speculation about what kind of stroke they used. While the short-necked pliosaurs may have been fast swimmers, the long-necked varieties were built more for maneuverability than for speed. Skeletons have also been discovered with gastroliths in their stomachs, probably to help with buoyancy.

Families

The earliest group of plesiosaurs, the plesiosaurids, had small heads and long necks. They evolved about 220 million years ago in the late Triassic, and were the first major group of plesiosaurs to became extinct, about 175 million years ago in the early Jurassic.

The next group of plesiosaurs was characterized by a large head and a short neck, and are collectively known as pliosaurs. The largest pliosaurs, such as Kronosaurus, had jaws 3 m (10 ft) long, and may have reached up to 12–15 m (40–50 ft) in length, and weighed more than 10,000 kg (11 tons). Isolated vertebrae and teeth from England may belong to specimens up to 20 m (65 ft) long, and weighing perhaps 20,000 kg (22 tons).

Pliosaurs had thick, conical teeth, and were the top carnivores of their domain. They fed on other marine reptiles, including their relatives — pliosaur teeth marks have been discovered on other plesiosaurs, like the cryptoclidids. The pliosaurs evolved about 200 million years ago, in the early Jurassic, and became extinct about 80 million years ago in the Cretaceous.

The third group also had a long neck and a tiny head, and were known as the cryptoclidids. Overall, they were shorter and more gracile than the plesiosaurids, but had longer necks in proportion to their body length. Their teeth were also small and slender, and may have been used to filter food from the sediment in shallow coastal waters. They first appeared about 160 million years ago at the end of the Jurassic period, and lasted until the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous, about 65 million years ago.

The last group, the elasmosaurs, took the long-neck and tiny head tendency to extremes. They were the longest, reaching from 13–17 m (42–56 ft) in length, but most of that was neck; they weighed much less than the more massive pliosaurs. They had up to 72 bones in their neck (vertebrae), more than any other animal. They lived at the same time as the cryptolidids, so they must have filled a different ecological niche. See Elasmosaurus for the typical genus.

Classification and history

The plesiosaur is one of the earliest fossils identified by paleontologists, along with the Mosasaurus, and the dinosaur Iguanodon. The first specimen, belonging to the Plesiosaurus genus, was found in 1821 by Mary Anning, in the Oxford Clay deposits near Lyme Regis, England, and she found the first good specimen just three years later. The species was formally described and named by Henry de la Beche and William Daniel Conybeare in 1821. The name they chose means "near lizard", dervived from the Greek plesios ("near") and sauros ("lizard"). The Plesiosauria taxon was named by Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1835.

Most of the plesiosaur material discovered in the 19th century was from the same deposits. Sir Richard Owen alone named almost a hundred new species. Despite this, however, plesiosaurs are very poorly known. Most of the new "species" were described based on a few isolated bones, without sufficient diagnostic characteristics to separate them from any of the other species that had previously been described. Many of these species have since been invalidated, but insufficent work has been done in the past century to clean up this taxonomic mess. The genera Plesiosaurus in particular is problematic. Most of the new species were placed there, so the taxon is a dumping ground for an almost random collection of bones.

Two other factors make it difficult to classify plesiosaurs. While they have been found on every continent, including Antarctica, almost all specimens are known from either the late Jurassic Oxford Clay in England where the first specimen was found, or from the middle Cretaceous Niobrara Chalk in Kansas, in the United States. Since only two links in a large evolutionary chain are well known, it is hard to extrapolate the large stretch in between.

Plesiosaurs also have another problem. The traditional way to classify plesiosaurs is by their gross body shape, but it appears the same body shape evolved multiple times in an example of convergent evolution. Recent analysis shows that the extremely long-necked elasmosaurs are actually descended from at least three unrelated lineages, making the taxon polyphyletic. Some pliosaurs may also be more closely related to long-necked species than other short-necked species. The four major groupings, while convenient, do not appear to be based on actual evolutionary relationships.

Recent discoveries

In 2002, the "Monster of Aramberri" was announced to the press. Discovered in 1982 at the village of Aramberri, in the Mexican state of Nuevo León, it was originally classified as a dinosaur. The specimen is actually a very large pliosaur, possibly reaching 15 m (50 ft) in length. The media published exaggerated reports claiming it was 25 m (80 ft) long, and weighed up to 150,000 kg, which made it the largest predator of all time. This error was perpetuated in BBC's documentary series Walking with Dinosaurs, which also prematurely classified it as a Liopleurodon ferox.

In 2004, what appears to be a 100 percent intact juvenile plesiosaur was discovered at Bridgwater Bay National Nature Reserve in the United Kingdom, by a local fisherman. The fossil measures 1.5 m (5 ft) in length, and may be related to the Rhomaleosaurus. It is probably the best preserved specimen of a plesiosaur ever discovered.

In fiction

The plesiosaur is popular among children and cryptozoologists, and appears in a number of children's books, and several films. It has appeared in films about lake monsters, including Magic in the Water (1995), and movies about the Loch Ness Monster, such as Loch Ness (1996). In both films, the creature primarily serves as a symbol of a lost, child-like sense of wonder.

Contrary to reports, the long-necked, sharp-toothed creature in the classic film King Kong (1933) — which flips a raft full of rescuers on their way to save Fay Wray, and then munches on the swimmers — is not a plesiosaur. Despite striking a profile in the mist very similar to the famous "Surgeon's Photo" of the Loch Ness Monster, it then chases the routed heroes onto dry land, where it is clearly intended to be a sauropod, like the Brontosaurus (now Apatosaurus).

Loch Ness and lake monsters

Main articles: sea monster, lake monster, Loch Ness Monster

Lake or sea monsters sightings are occasionally explained as plesiosaurs. While the survival of a small, unrecorded breeding colony of plesiosaurs for the 65,000,000 years since their apparent extinction is unlikely, the discovery of real and even more ancient living fossils like the Coelacanth, and previously unknown but enormous deep-sea animals like the colossal squid have have fueled imaginations. However, none of these reports have stood up to scientific scrutiny.

The 1977 discovery of a carcass with flippers and what appeared to be a long neck and head by the Japanese fishing trawler Zuiyo Maru off New Zealand created a plesiosaur craze in Japan, but later analysis suggested it was actually a decayed basking shark.

The Loch Ness Monster is commonly reported to resemble a plesiosaur, though just as frequently the creature described bears little or no resemblance. In addition, the lake is too cold for a cold-blooded animal to easily survive, air-breathing animals like plesiosaurs would be easily spotted when they surface to breathe, the lake is too small to support a breeding colony, and the loch itself was only formed 10,000 years ago during the last ice age. The sightings can be explained as some combination of waves, floating debris, mist-mirages, swimming animals (like the otter, which can reach 6 ft in length), and hoaxes.

The National Museum of Scotland confirmed that vertebrae discovered on the shores of Loch Ness in 2003 belong to a plesiosaur, though there are some questions about whether the fossils were planted. In any case, the 150,000,000 year-old fossils vastly predate the formation of the loch.

External links

- The Plesiosaur Site (http://www.plesiosaur.com/). Richard Forrest.

- Plesiosaur FAQ's (http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Hangar/9020/plesiosaur/). Raymond Thaddeus C. Ancog.

- Oceans of Kansas Paleontology (http://www.oceansofkansas.com/Oceans). Mike Everhart.

- "Plesiosaur fossil found in Bridgwater Bay (http://www.somerset.gov.uk/museums/PLESIO.htm)". Somersert Museums County Service. (best known fossil)

- "Fossil hunters turn up 50-ton monster of prehistoric deep (http://www.timesonline.co.uk/printFriendly/0,,1-2-527486,00.html)". Allan Hall and Mark Henderson. Times Online, December 30, 2002. (Monster of Aramberri)

- "A Jurassic fossil discovered in Loch Ness by a Scots pensioner could be the original Loch Ness monster, according to Nessie enthusiasts (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/scotland/3069803.stm)". BBC News, July 16, 2003. (Loch Ness, possible hoax)

- "Sea-monster or shark? an analysis of a supposed plesiosaur carcass netted in 1977 (http://paleo.cc/paluxy/plesios.htm)". Glen J. Kuban. Reports of the National Center for Science Education, May/June 1997, volume 17, number 3, pages 16–28.da:Plesiosaurus

de:Plesiosaurier nl:Plesiosauria no:Svaneřgle pt:Plesiossauro